For Subversion 1.5

(Compiled from r3074)

Copyright © 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008 Ben Collins-Sussman, Brian W. Fitzpatrick, C. Michael Pilato

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 559 Nathan Abbott Way, Stanford, California 94305, USA.

(TBA)

Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1. Fundamental Concepts

- 2. Basic Usage

- 3. Advanced Topics

- 4. Branching and Merging

- 5. Repository Administration

- The Subversion Repository, Defined

- Strategies for Repository Deployment

- Creating and Configuring Your Repository

- Repository Maintenance

- Moving and Removing Repositories

- Summary

- 6. Server Configuration

- Overview

- Choosing a Server Configuration

- svnserve, a Custom Server

- httpd, the Apache HTTP Server

- Path-Based Authorization

- Supporting Multiple Repository Access Methods

- 7. Customizing Your Subversion Experience

- 8. Embedding Subversion

- 9. Subversion Complete Reference

- The Subversion Command-Line Client: svn

- svn Options

- svn Subcommands

- svn add

- svn blame

- svn cat

- svn changelist

- svn checkout

- svn cleanup

- svn commit

- svn copy

- svn delete

- svn diff

- svn export

- svn help

- svn import

- svn info

- svn list

- svn lock

- svn log

- svn merge

- svn mergeinfo

- svn mkdir

- svn move

- svn propdel

- svn propedit

- svn propget

- svn proplist

- svn propset

- svn resolved

- svn revert

- svn status

- svn switch

- svn unlock

- svn update

- svnadmin

- svnlook

- svnsync

- svnserve

- svnversion

- mod_dav_svn

- Subversion Properties

- Repository Hooks

- A. Subversion Quick-Start Guide

- B. Subversion for CVS Users

- C. WebDAV and Autoversioning

- D. Copyright

- Index

List of Figures

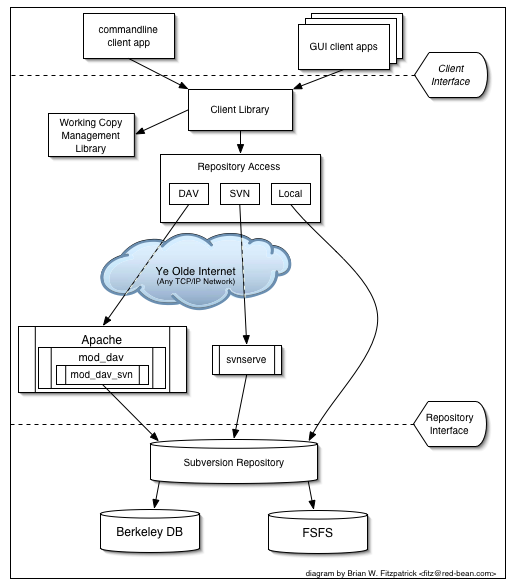

- 1. Subversion's architecture

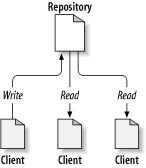

- 1.1. A typical client/server system

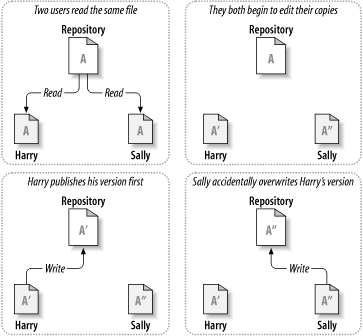

- 1.2. The problem to avoid

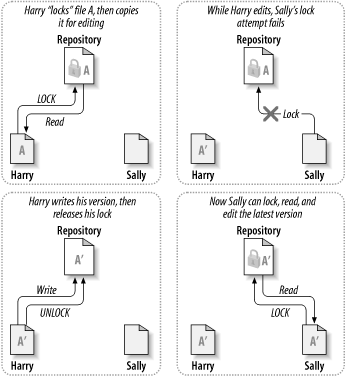

- 1.3. The lock-modify-unlock solution

- 1.4. The copy-modify-merge solution

- 1.5. The copy-modify-merge solution (continued)

- 1.6. The repository's filesystem

- 1.7. The repository

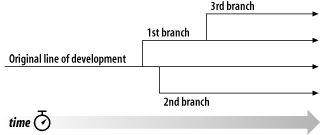

- 4.1. Branches of development

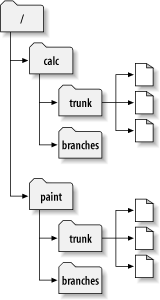

- 4.2. Starting repository layout

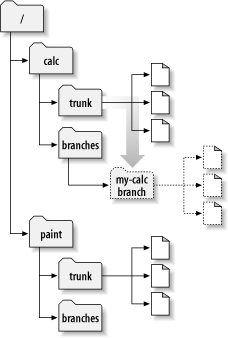

- 4.3. Repository with new copy

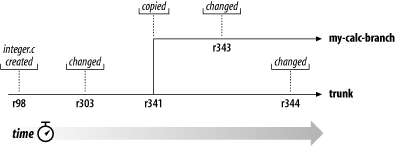

- 4.4. The branching of one file's history

- 8.1. Files and directories in two dimensions

- 8.2. Versioning time—the third dimension!

List of Tables

List of Examples

- 5.1. txn-info.sh (reporting outstanding transactions)

- 5.2. Mirror repository's pre-revprop-change hook script

- 5.3. Mirror repository's start-commit hook script

- 6.1. A sample configuration for anonymous access.

- 6.2. A sample configuration for authenticated access.

- 6.3. A sample configuration for mixed authenticated/anonymous access

- 6.4. Disabling path checks altogether

- 7.1. Sample registration entries (.reg) file.

- 7.2. diffwrap.sh

- 7.3. diffwrap.bat

- 7.4. diff3wrap.sh

- 7.5. diff3wrap.bat

- 8.1. Using the Repository Layer

- 8.2. Using the Repository Layer with Python

- 8.3. A Python status crawler

A bad Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) sheet is one that is composed not of the questions people actually ask, but of the questions the FAQ's author wish people would ask. Perhaps you've seen the type before:

Q: How can I use Glorbosoft XYZ to maximize team productivity?

A: Many of our customers want to know how they can maximize productivity through our patented office groupware innovations. The answer is simple. First, click on the

Filemenu, scroll down toIncrease Productivity, then…

The problem with such FAQs is that they are not, in a literal sense, FAQs at all. No one ever called the tech support line and asked, “How can we maximize productivity?”. Rather, people asked highly specific questions, such as “How can we change the calendaring system to send reminders two days in advance instead of one?” and so on. But it's a lot easier to make up imaginary Frequently Asked Questions than it is to discover the real ones. Compiling a true FAQ sheet requires a sustained, organized effort: over the lifetime of the software, incoming questions must be tracked, responses monitored, and all gathered into a coherent, searchable whole that reflects the collective experience of users in the wild. It calls for the patient, observant attitude of a field naturalist. No grand hypothesizing, no visionary pronouncements here—open eyes and accurate note-taking are what's needed most.

What I love about this book is that it grew out of just such a process, and shows it on every page. It is the direct result of the authors' encounters with users. It began with Ben Collins-Sussman's observation that people were asking the same basic questions over and over on the Subversion mailing lists: What are the standard workflows to use with Subversion? Do branches and tags work the same way as in other version control systems? How can I find out who made a particular change?

Frustrated at seeing the same questions day after day, Ben worked intensely over a month in the summer of 2002 to write The Subversion Handbook, a 60 page manual that covered all the basics of using Subversion. The manual made no pretense of being complete, but it was distributed with Subversion and got users over that initial hump in the learning curve. When O'Reilly decided to publish a full-length Subversion book, the path of least resistance was obvious: just expand the Subversion handbook.

The three coauthors of the new book were thus presented with an unusual opportunity. Officially, their task was to write a book top-down, starting from a table of contents and an initial draft. But they also had access to a steady stream—indeed, an uncontrollable geyser—of bottom-up source material. Subversion was already in the hands of thousands of early adopters, and those users were giving tons of feedback, not only about Subversion, but about its existing documentation.

During the entire time they wrote this book, Ben, Mike, and Brian haunted the Subversion mailing lists and chat rooms incessantly, carefully noting the problems users were having in real-life situations. Monitoring such feedback was part of their job descriptions at CollabNet anyway, and it gave them a huge advantage when they set out to document Subversion. The book they produced is grounded firmly in the bedrock of experience, not in the shifting sands of wishful thinking; it combines the best aspects of user manual and FAQ sheet. This duality might not be noticeable on a first reading. Taken in order, front to back, the book is simply a straightforward description of a piece of software. There's the overview, the obligatory guided tour, the chapter on administrative configuration, some advanced topics, and of course a command reference and troubleshooting guide. Only when you come back to it later, seeking the solution to some specific problem, does its authenticity shine out: the telling details that can only result from encounters with the unexpected, the examples honed from genuine use cases, and most of all the sensitivity to the user's needs and the user's point of view.

Of course, no one can promise that this book will answer

every question you have about Subversion. Sometimes, the

precision with which it anticipates your questions will seem

eerily telepathic; yet occasionally, you will stumble into a

hole in the community's knowledge and come away empty-handed.

When this happens, the best thing you can do is email

<users@subversion.tigris.org> and present your

problem. The authors are still there and still watching, and the

authors include not just the three listed on the cover, but many others

who contributed corrections and original material. From the

community's point of view, solving your problem is merely a

pleasant side effect of a much larger project—namely,

slowly adjusting this book, and ultimately Subversion itself, to

more closely match the way people actually use it. They are

eager to hear from you, not only because they can help you, but

because you can help them. With Subversion, as with all active

free software projects, you are not

alone.

Let this book be your first companion.

Table of Contents

“It is important not to let the perfect become the enemy of the good, even when you can agree on what perfect is. Doubly so when you can't. As unpleasant as it is to be trapped by past mistakes, you can't make any progress by being afraid of your own shadow during design.” | ||

| --Greg Hudson | ||

In the world of open source software, the Concurrent Versions System (CVS) was the tool of choice for version control for many years. And rightly so. CVS was open source software itself, and its nonrestrictive modus operandi and support for networked operation allowed dozens of geographically dispersed programmers to share their work. It fit the collaborative nature of the opensource world very well. CVS and its semi-chaotic development model have since become cornerstones of open source culture.

But CVS was not without its flaws, and simply fixing those flaws promised to be an enormous effort. Enter Subversion. Designed to be a successor to CVS, Subversion's originators set out to win the hearts of CVS users in two ways—by creating an open source system with a design (and “look and feel”) similar to CVS, and by attempting to avoid most of CVS's noticeable flaws. While the result isn't necessarily the next great evolution in version control design, Subversion is very powerful, very usable, and very flexible. And for the most part, almost all newly started open source projects now choose Subversion instead of CVS.

This book is written to document the 1.5 series of the Subversion version control system. We have made every attempt to be thorough in our coverage. However, Subversion has a thriving and energetic development community, so there are already a number of features and improvements planned for future versions that may change some of the commands and specific notes in this book.

This book is written for computer-literate folk who want to use Subversion to manage their data. While Subversion runs on a number of different operating systems, its primary user interface is command-line-based. That command-line tool (svn), and some auxiliary programs, are the focus of this book.

For consistency, the examples in this book assume that the reader

is using a Unix-like operating system and is relatively comfortable

with Unix and command-line interfaces. That said, the

svn program also runs on non-Unix platforms

such as Microsoft Windows. With a few minor exceptions, such as

the use of backward slashes (\) instead of

forward slashes (/) for path separators, the

input to and output from this tool when run on Windows are

identical to its Unix counterpart.

Most readers are probably programmers or system administrators who need to track changes to source code. This is the most common use for Subversion, and therefore it is the scenario underlying all of the book's examples. But Subversion can be used to manage changes to any sort of information—images, music, databases, documentation, and so on. To Subversion, all data is just data.

While this book is written with the assumption that the reader has never used a version control system, we've also tried to make it easy for users of CVS (and other systems) to make a painless leap into Subversion. Special sidebars may mention other version control systems from time to time, and Appendix B summarizes many of the differences between CVS and Subversion.

Note also that the source code examples used throughout the book are only examples. While they will compile with the proper compiler incantations, they are intended to illustrate a particular scenario and not necessarily serve as examples of good programming style or practices.

Technical books always face a certain dilemma: whether to cater to top-down or to bottom-up learners. A top-down learner prefers to read or skim documentation, getting a large overview of how the system works; only then does she actually start using the software. A bottom-learner is a “learn by doing” personmdash;someone who just wants to dive into the software and figure it out as she goes, referring to book sections when necessary. Most books tend to be written for one type of person or the other, and this book is undoubtedly biased towards top-down learners. (And if you're actually reading this section, you're probably already a top-down learner yourself!) However, if you're a bottom-up person, don't despair. While the book may be laid out as a broad survey of Subversion topics, the content of each section tends to be heavy with specific examples that you can try-by-doing. For the impatient folks who just want to get going, you can jump right to Appendix A, Subversion Quick-Start Guide.

Regardless of your learning style, this book aims to be useful to people of widely different backgrounds—from those with no previous experience in version control to experienced system administrators. Depending on your own background, certain chapters may be more or less important to you. The following can be considered a “recommended reading list” for various types of readers:

- Experienced System Administrators

The assumption here is that you've probably used version control before and are dying to get a Subversion server up and running ASAP. Chapter 5, Repository Administration and Chapter 6, Server Configuration will show you how to create your first repository and make it available over the network. After that's done, Chapter 2, Basic Usage and Appendix B, Subversion for CVS Users are the fastest routes to learning the Subversion client.

- New users

Your administrator has probably set up Subversion already, and you need to learn how to use the client. If you've never used a version control system, then Chapter 1, Fundamental Concepts is a vital introduction to the ideas behind version control. Chapter 2, Basic Usage is a guided tour of the Subversion client.

- Advanced users

Whether you're a user or administrator, eventually your project will grow larger. You're going to want to learn how to do more advanced things with Subversion, such as how to use Subversion's property support (Chapter 3, Advanced Topics), how to use branches and perform merges (Chapter 4, Branching and Merging), how to configure runtime options (Chapter 7, Customizing Your Subversion Experience), and other things. These chapters aren't critical at first, but be sure to read them once you're comfortable with the basics.

- Developers

Presumably, you're already familiar with Subversion, and now want to either extend it or build new software on top of its many APIs. Chapter 8, Embedding Subversion is just for you.

The book ends with reference material—Chapter 9, Subversion Complete Reference is a reference guide for all Subversion commands, and the appendices cover a number of useful topics. These are the chapters you're mostly likely to come back to after you've finished the book.

This section covers the various conventions used in this book.

The following typographic conventions are used in this book:

- Constant width

Used for commands, command output, and options

Constant width italicUsed for replaceable items in code and text

ItalicUsed for file and directory names as well as for new terms

The chapters that follow and their contents are listed here:

- Preface

Covers the history of Subversion as well as its features, architecture, and components.

- Chapter 1, Fundamental Concepts

Explains the basics of version control and different versioning models, along with Subversion's repository, working copies, and revisions.

- Chapter 2, Basic Usage

Walks you through a day in the life of a Subversion user. It demonstrates how to use a Subversion client to obtain, modify, and commit data.

- Chapter 3, Advanced Topics

Covers more complex features that regular users will eventually come into contact with, such as versioned metadata, file locking, and peg revisions.

- Chapter 4, Branching and Merging

Discusses branches, merges, and tagging, including best practices for branching and merging, common use cases, how to undo changes, and how to easily swing from one branch to the next.

- Chapter 5, Repository Administration

Describes the basics of the Subversion repository, how to create, configure, and maintain a repository, and the tools you can use to do all of this.

- Chapter 6, Server Configuration

Explains how to configure your Subversion server and offers different ways to access your repository:

HTTP, thesvnprotocol, and local disk access. It also covers the details of authentication, authorization and anonymous access.- Chapter 7, Customizing Your Subversion Experience

Explores the Subversion client configuration files, the handling of internationalized text, and how to make external tools cooperate with Subversion.

- Chapter 8, Embedding Subversion

Describes the internals of Subversion, the Subversion filesystem, and the working copy administrative areas from a programmer's point of view. Demonstrates how to use the public APIs to write a program that uses Subversion, and most importantly, how to contribute to the development of Subversion.

- Chapter 9, Subversion Complete Reference

Explains in great detail every subcommand of svn, svnadmin, and svnlook with plenty of examples for the whole family!

- Appendix A, Subversion Quick-Start Guide

For the impatient, a whirlwind explanation of how to install Subversion and start using it immediately. You have been warned.

- Appendix B, Subversion for CVS Users

Covers the similarities and differences between Subversion and CVS, with numerous suggestions on how to break all the bad habits you picked up from years of using CVS. Included are descriptions of Subversion revision numbers, versioned directories, offline operations, update versus status, branches, tags, metadata, conflict resolution, and authentication.

- Appendix C, WebDAV and Autoversioning

Describes the details of WebDAV and DeltaV and how you can configure your Subversion repository to be mounted read/write as a DAV share.

- Appendix D, Copyright

A copy of the Creative Commons Attribution License., under which this book is licensed.

This book started out as bits of documentation written by Subversion project developers, which were then coalesced into a single work and rewritten. As such, it has always been under a free license (see Appendix D, Copyright). In fact, the book was written in the public eye, originally as a part of Subversion project itself. This means two things:

You will always find the latest version of this book in the book's own Subversion repository.

You can make changes to this book and redistribute it however you wish—it's under a free license. Your only obligation is to maintain proper attribution to the original authors. Of course, rather than distribute your own private version of this book, we'd much rather you send feedback and patches to the Subversion developer community.

The online home of this book's development and most of the

volunteer-driven translation efforts around it is

http://svnbook.red-bean.com. There, you can find

links to the latest releases and tagged versions of the book in

various formats, as well as instructions for accessing the

book's Subversion repository (where lives its DocBook XML source

code). Feedback is welcome—encouraged, even. Please

submit all comments, complaints, and patches against the book

sources to <svnbook-dev@red-bean.com>.

This book would not be possible (nor very useful) if Subversion did not exist. For that, the authors would like to thank Brian Behlendorf and CollabNet for the vision to fund such a risky and ambitious new open source project; Jim Blandy for the original Subversion name and design—we love you, Jim; and Karl Fogel for being such a good friend and a great community leader, in that order. [1]

Thanks to O'Reilly and our editors, Linda Mui and Tatiana Apandi, for their patience and support.

Finally, we thank the countless people who contributed to this book with informal reviews, suggestions, and fixes. While this is undoubtedly not a complete list, this book would be incomplete and incorrect without the help of: David Anderson, Jani Averbach, Ryan Barrett, Francois Beausoleil, Jennifer Bevan, Matt Blais, Zack Brown, Martin Buchholz, Brane Cibej, John R. Daily, Peter Davis, Olivier Davy, Robert P. J. Day, Mo DeJong, Brian Denny, Joe Drew, Nick Duffek, Ben Elliston, Justin Erenkrantz, Shlomi Fish, Julian Foad, Chris Foote, Martin Furter, Vlad Georgescu, Dave Gilbert, Eric Gillespie, David Glasser, Matthew Gregan, Art Haas, Eric Hanchrow, Greg Hudson, Alexis Huxley, Jens B. Jorgensen, Tez Kamihira, David Kimdon, Mark Benedetto King, Andreas J. Koenig, Nuutti Kotivuori, Matt Kraai, Scott Lamb, Vincent Lefevre, Morten Ludvigsen, Paul Lussier, Bruce A. Mah, Philip Martin, Feliciano Matias, Patrick Mayweg, Gareth McCaughan, Jon Middleton, Tim Moloney, Christopher Ness, Mats Nilsson, Joe Orton, Amy Lyn Pilato, Kevin Pilch-Bisson, Dmitriy Popkov, Michael Price, Mark Proctor, Steffen Prohaska, Daniel Rall, Jack Repenning, Tobias Ringstrom, Garrett Rooney, Joel Rosdahl, Christian Sauer, Larry Shatzer, Russell Steicke, Sander Striker, Erik Sjoelund, Johan Sundstroem, John Szakmeister, Mason Thomas, Eric Wadsworth, Colin Watson, Alex Waugh, Chad Whitacre, Josef Wolf, Blair Zajac, and the entire Subversion community.

Thanks to my wife Frances, who, for many months, got to hear, “But honey, I'm still working on the book,” rather than the usual, “But honey, I'm still doing email.” I don't know where she gets all that patience! She's my perfect counterbalance.

Thanks to my extended family and friends for their sincere encouragement, despite having no actual interest in the subject. (You know, the ones who say, “Ooh, you wrote a book?”, and then when you tell them it's a computer book, sort of glaze over.)

Thanks to all my close friends, who make me a rich, rich man. Don't look at me that way—you know who you are.

Thanks to my parents for the perfect low-level formatting and being unbelievable role models. Thanks to my son for the opportunity to pass that on.

Huge thanks to my wife Marie for being incredibly understanding, supportive, and most of all, patient. Thank you to my brother Eric who first introduced me to Unix programming way back when. Thanks to my Mom and Grandmother for all their support, not to mention enduring a Christmas holiday where I came home and promptly buried my head in my laptop to work on the book.

To Mike and Ben: It was a pleasure working with you on the book. Heck, it's a pleasure working with you at work!

To everyone in the Subversion community and the Apache Software Foundation, thanks for having me. Not a day goes by where I don't learn something from at least one of you.

Lastly, thanks to my Grandfather who always told me that “freedom equals responsibility.” I couldn't agree more.

Special thanks to Amy, my best friend and wife of nearly ten incredible years, for her love and patient support, for putting up with the late nights, and for graciously enduring the version control processes I've imposed on her. Don't worry, Sweetheart—you'll be a TortoiseSVN wizard in no time!

Gavin, you can probably read half of the words in this book yourself now; sadly, it's the other half that provide the key concepts. But when you've finally gotten a handle on the written form of this crazy language we speak, I hope you're as proud of your Daddy as he is of you.

Aidan, what can I say? I'm sorry this book doesn't have any pictures or stories of locomotives. I still love you, son. (And I recommend the works of Rev. W. V. Awdry to fuel your current passion.)

Mom and Dad, thanks for your constant support and enthusiasm. Mom- and Dad-in-law, thanks for all of the same plus your fabulous daughter.

Hats off to Shep Kendall, through whom the world of

computers was first opened to me; Ben Collins-Sussman, my

tour-guide through the open source world; Karl Fogel, you

are my .emacs; Greg

Stein, for oozing practical programming know-how; Brian

Fitzpatrick, for sharing this writing experience with me.

To the many folks from whom I am constantly picking up new

knowledge—keep dropping it!

Finally, to the One who perfectly demonstrates creative excellence—thank You.

Subversion is a free/open source version control system. That is, Subversion manages files and directories, and the changes made to them, over time. This allows you to recover older versions of your data or examine the history of how your data changed. In this regard, many people think of a version control system as a sort of “time machine.”

Subversion can operate across networks, which allows it to be used by people on different computers. At some level, the ability for various people to modify and manage the same set of data from their respective locations fosters collaboration. Progress can occur more quickly without a single conduit through which all modifications must occur. And because the work is versioned, you need not fear that quality is the trade-off for losing that conduit—if some incorrect change is made to the data, just undo that change.

Some version control systems are also software configuration management (SCM) systems. These systems are specifically tailored to manage trees of source code and have many features that are specific to software development—such as natively understanding programming languages, or supplying tools for building software. Subversion, however, is not one of these systems. It is a general system that can be used to manage any collection of files. For you, those files might be source code—for others, anything from grocery shopping lists to digital video mixdowns and beyond.

If you're a user or system administrator pondering the use of Subversion, the first question you should ask yourself is: "Is this the right tool for the job?" Subversion is a fantastic hammer, but be careful not to view every problem as a nail.

If you need to archive old versions of files and directories, possibly resurrect them, or examine logs of how they've changed over time, then Subversion is exactly the right tool for you. If you need to collaborate with people on documents (usually over a network) and keep track of who made which changes, then Subversion is also appropriate. This is why Subversion is so often used in software development environments— programming is an inherently social activity, and Subversion makes it easy to collaborate with other programmers. Of course, there's a cost to using Subversion as well: administrative overhead. You'll need to manage a data repository to store the information and all its history, and be diligent about backing it up. When working with the data on a daily basis, you won't be able to copy, move, rename, or delete files the way you usually do. Instead, you'll have to do all of those things through Subversion.

Assuming you're fine with the extra workflow, you should still make sure you're not using Subversion to solve a problem that other tools solve better. For example, because Subversion replicates data to all the collaborators involved, a common misuse is to treat it as a generic distribution system. People will sometimes use Subversion to distribute huge collections of photos, digital music, or software packages. The problem is that this sort of data usually isn't changing at all. The collection itself grows over time, but the individual files within the collection aren't being changed. In this case, using Subversion is “overkill.” [2] There are simpler tools that efficiently replicate data without the overhead of tracking changes, such as rsync or unison.

In early 2000, CollabNet, Inc. (http://www.collab.net) began seeking developers to write a replacement for CVS. CollabNet offers a collaboration software suite called CollabNet Enterprise Edition (CEE), of which one component is version control. Although CEE used CVS as its initial version control system, CVS's limitations were obvious from the beginning, and CollabNet knew it would eventually have to find something better. Unfortunately, CVS had become the de facto standard in the open source world largely because there wasn't anything better, at least not under a free license. So CollabNet determined to write a new version control system from scratch, retaining the basic ideas of CVS, but without the bugs and misfeatures.

In February 2000, they contacted Karl Fogel, the author of Open Source Development with CVS (Coriolis, 1999), and asked if he'd like to work on this new project. Coincidentally, at the time Karl was already discussing a design for a new version control system with his friend Jim Blandy. In 1995, the two had started Cyclic Software, a company providing CVS support contracts, and although they later sold the business, they still used CVS every day at their jobs. Their frustration with CVS had led Jim to think carefully about better ways to manage versioned data, and he'd already come up with not only the name “Subversion,” but also with the basic design of the Subversion data store. When CollabNet called, Karl immediately agreed to work on the project, and Jim got his employer, Red Hat Software, to essentially donate him to the project for an indefinite period of time. CollabNet hired Karl and Ben Collins-Sussman, and detailed design work began in May 2000. With the help of some well-placed prods from Brian Behlendorf and Jason Robbins of CollabNet, and from Greg Stein (at the time an independent developer active in the WebDAV/DeltaV specification process), Subversion quickly attracted a community of active developers. It turned out that many people had encountered the same frustrating experiences with CVS and welcomed the chance to finally do something about it.

The original design team settled on some simple goals. They didn't want to break new ground in version control methodology, they just wanted to fix CVS. They decided that Subversion would match CVS's features and preserve the same development model, but not duplicate CVS's most obvious flaws. And although it did not need to be a drop-in replacement for CVS, it should be similar enough that any CVS user could make the switch with little effort.

After 14 months of coding, Subversion became “self-hosting” on August 31, 2001. That is, Subversion developers stopped using CVS to manage Subversion's own source code and started using Subversion instead.

While CollabNet started the project, and still funds a large chunk of the work (it pays the salaries of a few full-time Subversion developers), Subversion is run like most open source projects, governed by a loose, transparent set of rules that encourage meritocracy. CollabNet's copyright license is fully compliant with the Debian Free Software Guidelines. In other words, anyone is free to download, modify, and redistribute Subversion as he pleases; no permission from CollabNet or anyone else is required.

When discussing the features that Subversion brings to the version control table, it is often helpful to speak of them in terms of how they improve upon CVS's design. If you're not familiar with CVS, you may not understand all of these features. And if you're not familiar with version control at all, your eyes may glaze over unless you first read Chapter 1, Fundamental Concepts, in which we provide a gentle introduction to version control.

Subversion provides:

- Directory versioning

CVS tracks only the history of individual files, but Subversion implements a “virtual” versioned filesystem that tracks changes to whole directory trees over time. Files and directories are versioned.

- True version history

Since CVS is limited to file versioning, operations such as copies and renames—which might happen to files, but which are really changes to the contents of some containing directory—aren't supported in CVS. Additionally, in CVS you cannot replace a versioned file with some new thing of the same name without the new item inheriting the history of the old—perhaps completely unrelated—file. With Subversion, you can add, delete, copy, and rename both files and directories. And every newly added file begins with a fresh, clean history all its own.

- Atomic commits

A collection of modifications either goes into the repository completely or not at all. This allows developers to construct and commit changes as logical chunks and prevents problems that can occur when only a portion of a set of changes is successfully sent to the repository.

- Versioned metadata

Each file and directory has a set of properties—keys and their values—associated with it. You can create and store any arbitrary key/value pairs you wish. Properties are versioned over time, just like file contents.

- Choice of network layers

Subversion has an abstracted notion of repository access, making it easy for people to implement new network mechanisms. Subversion can plug into the Apache HTTP Server as an extension module. This gives Subversion a big advantage in stability and interoperability, and instant access to existing features provided by that server—authentication, authorization, wire compression, and so on. A more lightweight, standalone Subversion server process is also available. This server speaks a custom protocol that can be easily tunneled over SSH.

- Consistent data handling

Subversion expresses file differences using a binary differencing algorithm, which works identically on both text (human-readable) and binary (human-unreadable) files. Both types of files are stored equally compressed in the repository, and differences are transmitted in both directions across the network.

- Efficient branching and tagging

The cost of branching and tagging need not be proportional to the project size. Subversion creates branches and tags by simply copying the project, using a mechanism similar to a hard link. Thus these operations take only a very small, constant amount of time.

- Hackability

Subversion has no historical baggage; it is implemented as a collection of shared C libraries with well-defined APIs. This makes Subversion extremely maintainable and usable by other applications and languages.

Figure 1, “Subversion's architecture” illustrates a “mile-high” view of Subversion's design.

On one end is a Subversion repository that holds all of your versioned data. On the other end is your Subversion client program, which manages local reflections of portions of that versioned data (called “working copies”). Between these extremes are multiple routes through various Repository Access (RA) layers. Some of these routes go across computer networks and through network servers which then access the repository. Others bypass the network altogether and access the repository directly.

Subversion, once installed, has a number of different pieces. The following is a quick overview of what you get. Don't be alarmed if the brief descriptions leave you scratching your head—there are plenty more pages in this book devoted to alleviating that confusion.

- svn

The command-line client program.

- svnversion

A program for reporting the state (in terms of revisions of the items present) of a working copy.

- svnlook

A tool for directly inspecting a Subversion repository.

- svnadmin

A tool for creating, tweaking, or repairing a Subversion repository.

- svndumpfilter

A program for filtering Subversion repository dump streams.

- mod_dav_svn

A plug-in module for the Apache HTTP Server, used to make your repository available to others over a network.

- svnserve

A custom standalone server program, runnable as a daemon process or invokable by SSH; another way to make your repository available to others over a network.

- svnsync

A program for incrementally mirroring one repository to another over a network.

Assuming you have Subversion installed correctly, you should be ready to start. The next two chapters will walk you through the use of svn, Subversion's command-line client program.

Table of Contents

This chapter is a short, casual introduction to Subversion. If you're new to version control, this chapter is definitely for you. We begin with a discussion of general version control concepts, work our way into the specific ideas behind Subversion, and show some simple examples of Subversion in use.

Even though the examples in this chapter show people sharing collections of program source code, keep in mind that Subversion can manage any sort of file collection—it's not limited to helping computer programmers.

Subversion is a centralized system for sharing information. At its core is a repository, which is a central store of data. The repository stores information in the form of a filesystem tree—a typical hierarchy of files and directories. Any number of clients connect to the repository, and then read or write to these files. By writing data, a client makes the information available to others; by reading data, the client receives information from others. Figure 1.1, “A typical client/server system” illustrates this.

So why is this interesting? So far, this sounds like the definition of a typical file server. And indeed, the repository is a kind of file server, but it's not your usual breed. What makes the Subversion repository special is that it remembers every change ever written to it—every change to every file, and even changes to the directory tree itself, such as the addition, deletion, and rearrangement of files and directories.

When a client reads data from the repository, it normally sees only the latest version of the filesystem tree. But the client also has the ability to view previous states of the filesystem. For example, a client can ask historical questions such as “What did this directory contain last Wednesday?” or “Who was the last person to change this file, and what changes did he make?” These are the sorts of questions that are at the heart of any version control system: systems that are designed to track changes to data over time.

The core mission of a version control system is to enable collaborative editing and sharing of data. But different systems use different strategies to achieve this. It's important to understand these different strategies for a couple of reasons. First, it will help you compare and contrast existing version control systems, in case you encounter other systems similar to Subversion. Beyond that, it will also help you make more effective use of Subversion, since Subversion itself supports a couple of different ways of working.

All version control systems have to solve the same fundamental problem: how will the system allow users to share information, but prevent them from accidentally stepping on each other's feet? It's all too easy for users to accidentally overwrite each other's changes in the repository.

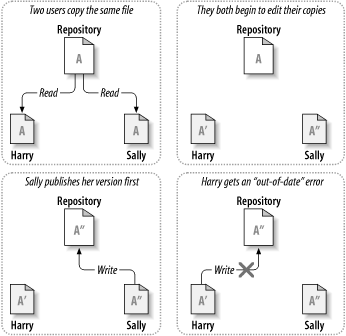

Consider the scenario shown in Figure 1.2, “The problem to avoid”. Suppose we have two coworkers, Harry and Sally. They each decide to edit the same repository file at the same time. If Harry saves his changes to the repository first, then it's possible that (a few moments later) Sally could accidentally overwrite them with her own new version of the file. While Harry's version of the file won't be lost forever (because the system remembers every change), any changes Harry made won't be present in Sally's newer version of the file, because she never saw Harry's changes to begin with. Harry's work is still effectively lost—or at least missing from the latest version of the file—and probably by accident. This is definitely a situation we want to avoid!

Many version control systems use a lock-modify-unlock model to address the problem of many authors clobbering each other's work. In this model, the repository allows only one person to change a file at a time. This exclusivity policy is managed using locks. Harry must “lock” a file before he can begin making changes to it. If Harry has locked a file, then Sally cannot also lock it, and therefore cannot make any changes to that file. All she can do is read the file and wait for Harry to finish his changes and release his lock. After Harry unlocks the file, Sally can take her turn by locking and editing the file. Figure 1.3, “The lock-modify-unlock solution” demonstrates this simple solution.

The problem with the lock-modify-unlock model is that it's a bit restrictive and often becomes a roadblock for users:

Locking may cause administrative problems. Sometimes Harry will lock a file and then forget about it. Meanwhile, because Sally is still waiting to edit the file, her hands are tied. And then Harry goes on vacation. Now Sally has to get an administrator to release Harry's lock. The situation ends up causing a lot of unnecessary delay and wasted time.

Locking may cause unnecessary serialization. What if Harry is editing the beginning of a text file, and Sally simply wants to edit the end of the same file? These changes don't overlap at all. They could easily edit the file simultaneously, and no great harm would come, assuming the changes were properly merged together. There's no need for them to take turns in this situation.

Locking may create a false sense of security. Suppose Harry locks and edits file A, while Sally simultaneously locks and edits file B. But what if A and B depend on one another, and the changes made to each are semantically incompatible? Suddenly A and B don't work together anymore. The locking system was powerless to prevent the problem—yet it somehow provided a false sense of security. It's easy for Harry and Sally to imagine that by locking files, each is beginning a safe, insulated task, and thus they need not bother discussing their incompatible changes early on. Locking often becomes a substitute for real communication.

Subversion, CVS, and many other version control systems use a copy-modify-merge model as an alternative to locking. In this model, each user's client contacts the project repository and creates a personal working copy—a local reflection of the repository's files and directories. Users then work simultaneously and independently, modifying their private copies. Finally, the private copies are merged together into a new, final version. The version control system often assists with the merging, but ultimately, a human being is responsible for making it happen correctly.

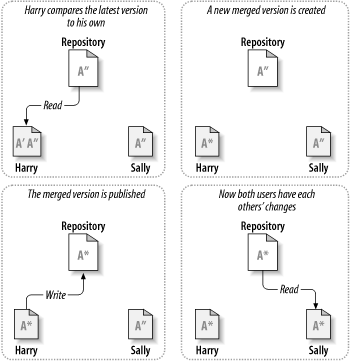

Here's an example. Say that Harry and Sally each create working copies of the same project, copied from the repository. They work concurrently and make changes to the same file A within their copies. Sally saves her changes to the repository first. When Harry attempts to save his changes later, the repository informs him that his file A is out-of-date. In other words, that file A in the repository has somehow changed since he last copied it. So Harry asks his client to merge any new changes from the repository into his working copy of file A. Chances are that Sally's changes don't overlap with his own; once he has both sets of changes integrated, he saves his working copy back to the repository. Figure 1.4, “The copy-modify-merge solution” and Figure 1.5, “The copy-modify-merge solution (continued)” show this process.

But what if Sally's changes do overlap with Harry's changes? What then? This situation is called a conflict, and it's usually not much of a problem. When Harry asks his client to merge the latest repository changes into his working copy, his copy of file A is somehow flagged as being in a state of conflict: he'll be able to see both sets of conflicting changes and manually choose between them. Note that software can't automatically resolve conflicts; only humans are capable of understanding and making the necessary intelligent choices. Once Harry has manually resolved the overlapping changes—perhaps after a discussion with Sally—he can safely save the merged file back to the repository.

The copy-modify-merge model may sound a bit chaotic, but in practice, it runs extremely smoothly. Users can work in parallel, never waiting for one another. When they work on the same files, it turns out that most of their concurrent changes don't overlap at all; conflicts are infrequent. And the amount of time it takes to resolve conflicts is usually far less than the time lost by a locking system.

In the end, it all comes down to one critical factor: user communication. When users communicate poorly, both syntactic and semantic conflicts increase. No system can force users to communicate perfectly, and no system can detect semantic conflicts. So there's no point in being lulled into a false sense of security that a locking system will somehow prevent conflicts; in practice, locking seems to inhibit productivity more than anything else.

It's time to move from the abstract to the concrete. In this section, we'll show real examples of Subversion being used.

Throughout this book, Subversion uses URLs to identify versioned files and directories in Subversion repositories. For the most part, these URLs use the standard syntax, allowing for server names and port numbers to be specified as part of the URL:

$ svn checkout http://svn.example.com:9834/repos …

But there are some nuances in Subversion's handling of URLs

that are notable. For example, URLs containing the

file:// access method (used for local

repositories) must, in accordance with convention, have either a

server name of localhost or no server name at

all:

$ svn checkout file:///var/svn/repos … $ svn checkout file://localhost/var/svn/repos …

Also, users of the file:// scheme on

Windows platforms will need to use an unofficially

“standard” syntax for accessing repositories

that are on the same machine, but on a different drive than

the client's current working drive. Either of the two

following URL path syntaxes will work, where

X is the drive on which the repository

resides:

C:\> svn checkout file:///X:/var/svn/repos … C:\> svn checkout "file:///X|/var/svn/repos" …

In the second syntax, you need to quote the URL so that the vertical bar character is not interpreted as a pipe. Also, note that a URL uses forward slashes even though the native (non-URL) form of a path on Windows uses backslashes.

Note

Subversion's file:// URLs cannot be

used in a regular web browser the way typical

file:// URLs can. When you attempt to view

a file:// URL in a regular web browser, it

reads and displays the contents of the file at that location

by examining the filesystem directly. However, Subversion's

resources exist in a virtual filesystem (see the section called “Repository Layer”), and your browser

will not understand how to interact with that

filesystem.

Finally, it should be noted that the Subversion client will automatically encode URLs as necessary, just like a web browser does. For example, if a URL contains a space or upper-ASCII character as in the following:

$ svn checkout "http://host/path with space/project/españa"

then Subversion will escape the unsafe characters and behave as if you had typed:

$ svn checkout http://host/path%20with%20space/project/espa%C3%B1a

If the URL contains spaces, be sure to place it within quote marks, so that your shell treats the whole thing as a single argument to the svn program.

You've already read about working copies; now we'll demonstrate how the Subversion client creates and uses them.

A Subversion working copy is an ordinary directory tree on your local system, containing a collection of files. You can edit these files however you wish, and if they're source code files, you can compile your program from them in the usual way. Your working copy is your own private work area: Subversion will never incorporate other people's changes, nor make your own changes available to others, until you explicitly tell it to do so. You can even have multiple working copies of the same project.

After you've made some changes to the files in your working copy and verified that they work properly, Subversion provides you with commands to “publish” your changes to the other people working with you on your project (by writing to the repository). If other people publish their own changes, Subversion provides you with commands to merge those changes into your working directory (by reading from the repository).

A working copy also contains some extra files, created and

maintained by Subversion, to help it carry out these commands.

In particular, each directory in your working copy contains a

subdirectory named .svn, also known as

the working copy's administrative

directory. The files in each administrative

directory help Subversion recognize which files contain

unpublished changes, and which files are out of date with

respect to others' work.

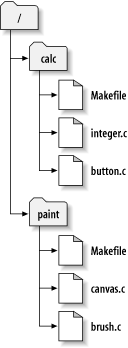

A typical Subversion repository often holds the files (or source code) for several projects; usually, each project is a subdirectory in the repository's filesystem tree. In this arrangement, a user's working copy will usually correspond to a particular subtree of the repository.

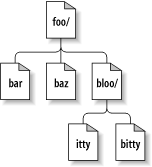

For example, suppose you have a repository that contains

two software projects, paint and

calc. Each project lives in its own

top-level subdirectory, as shown in Figure 1.6, “The repository's filesystem”.

To get a working copy, you must check

out some subtree of the repository. (The term

check out may sound like it has something to do

with locking or reserving resources, but it doesn't; it simply

creates a private copy of the project for you.) For example,

if you check out /calc, you will get a

working copy like this:

$ svn checkout http://svn.example.com/repos/calc A calc/Makefile A calc/integer.c A calc/button.c Checked out revision 56. $ ls -A calc Makefile integer.c button.c .svn/

The list of letter As in the left margin indicates that

Subversion is adding a number of items to your working copy.

You now have a personal copy of the

repository's /calc directory, with one

additional entry—.svn—which

holds the extra information needed by Subversion, as mentioned

earlier.

Suppose you make changes to button.c.

Since the .svn directory remembers the

file's original modification date and contents, Subversion can

tell that you've changed the file. However, Subversion does

not make your changes public until you explicitly tell it to.

The act of publishing your changes is more commonly known as

committing (or checking

in) changes to the repository.

To publish your changes to others, you can use Subversion's commit command.

$ svn commit button.c -m "Fixed a typo in button.c." Sending button.c Transmitting file data . Committed revision 57.

Now your changes to button.c have

been committed to the repository, with a note describing your

change (namely, that you fixed a typo). If another user

checks out a working copy of /calc, they

will see your changes in the latest version of the

file.

Suppose you have a collaborator, Sally, who checked out a

working copy of /calc at the same time

you did. When you commit your change to

button.c, Sally's working copy is left

unchanged; Subversion modifies working copies only at the

user's request.

To bring her project up to date, Sally can ask Subversion to update her working copy, by using the update command. This will incorporate your changes into her working copy, as well as any others that have been committed since she checked it out.

$ pwd /home/sally/calc $ ls -A .svn/ Makefile integer.c button.c $ svn update U button.c Updated to revision 57.

The output from the svn update command

indicates that Subversion updated the contents of

button.c. Note that Sally didn't need to

specify which files to update; Subversion uses the information

in the .svn directory as well as further

information in the repository, to decide which files need to

be brought up to date.

An svn commit operation publishes changes to any number of files and directories as a single atomic transaction. In your working copy, you can change files' contents; create, delete, rename, and copy files and directories; then commit a complete set of changes as an atomic transaction.

By atomic transaction, we mean simply this: either all of the changes happen in the repository, or none of them happen. Subversion tries to retain this atomicity in the face of program crashes, system crashes, network problems, and other users' actions.

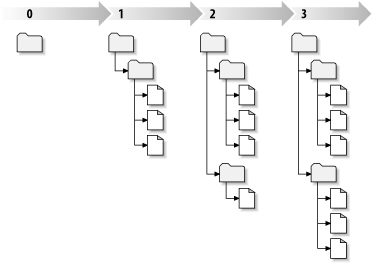

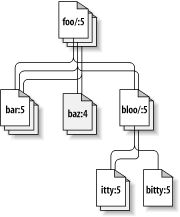

Each time the repository accepts a commit, this creates a new state of the filesystem tree, called a revision. Each revision is assigned a unique natural number, one greater than the number of the previous revision. The initial revision of a freshly created repository is numbered 0 and consists of nothing but an empty root directory.

Figure 1.7, “The repository” illustrates a nice way to visualize the repository. Imagine an array of revision numbers, starting at 0, stretching from left to right. Each revision number has a filesystem tree hanging below it, and each tree is a “snapshot” of the way the repository looked after a commit.

It's important to note that working copies do not always correspond to any single revision in the repository; they may contain files from several different revisions. For example, suppose you check out a working copy from a repository whose most recent revision is 4:

calc/Makefile:4

integer.c:4

button.c:4

At the moment, this working directory corresponds exactly

to revision 4 in the repository. However, suppose you make a

change to button.c, and commit that

change. Assuming no other commits have taken place, your

commit will create revision 5 of the repository, and your

working copy will now look like this:

calc/Makefile:4

integer.c:4

button.c:5

Suppose that, at this point, Sally commits a change to

integer.c, creating revision 6. If you

use svn update to bring your working copy

up to date, then it will look like this:

calc/Makefile:6

integer.c:6

button.c:6

Sally's change to integer.c will

appear in your working copy, and your change will still be

present in button.c. In this example,

the text of Makefile is identical in

revisions 4, 5, and 6, but Subversion will mark your working

copy of Makefile with revision 6 to

indicate that it is still current. So, after you do a clean

update at the top of your working copy, it will generally

correspond to exactly one revision in the repository.

For each file in a working directory, Subversion records

two essential pieces of information in the

.svn/ administrative area:

What revision your working file is based on (this is called the file's working revision) and

A timestamp recording of when the local copy was last updated by the repository

Given this information, by talking to the repository, Subversion can tell which of the following four states a working file is in:

- Unchanged, and current

The file is unchanged in the working directory, and no changes to that file have been committed to the repository since its working revision. An svn commit of the file will do nothing, and an svn update of the file will do nothing.

- Locally changed, and current

The file has been changed in the working directory, and no changes to that file have been committed to the repository since you last updated. There are local changes that have not been committed to the repository, thus an svn commit of the file will succeed in publishing your changes, and an svn update of the file will do nothing.

- Unchanged, and out-of-date

The file has not been changed in the working directory, but it has been changed in the repository. The file should eventually be updated in order to make it current with the latest public revision. An svn commit of the file will do nothing, and an svn update of the file will fold the latest changes into your working copy.

- Locally changed, and out-of-date

The file has been changed both in the working directory and in the repository. An svn commit of the file will fail with an “out-of-date” error. The file should be updated first; an svn update command will attempt to merge the public changes with the local changes. If Subversion can't complete the merge in a plausible way automatically, it leaves it to the user to resolve the conflict.

This may sound like a lot to keep track of, but the svn status command will show you the state of any item in your working copy. For more information on that command, see the section called “See an overview of your changes”.

As a general principle, Subversion tries to be as flexible as possible. One special kind of flexibility is the ability to have a working copy containing files and directories with a mix of different working revision numbers. Unfortunately, this flexibility tends to confuse a number of new users. If the earlier example showing mixed revisions perplexed you, here's a primer on both why the feature exists and how to make use of it.

One of the fundamental rules of Subversion is that a “push” action does not cause a “pull,” nor the other way around. Just because you're ready to submit new changes to the repository doesn't mean you're ready to receive changes from other people. And if you have new changes still in progress, then svn update should gracefully merge repository changes into your own, rather than forcing you to publish them.

The main side effect of this rule is that it means a working copy has to do extra bookkeeping to track mixed revisions as well as be tolerant of the mixture. It's made more complicated by the fact that directories themselves are versioned.

For example, suppose you have a working copy entirely at

revision 10. You edit the

file foo.html and then perform

an svn commit, which creates revision 15

in the repository. After the commit succeeds, many new

users would expect the working copy to be entirely at

revision 15, but that's not the case! Any number of changes

might have happened in the repository between revisions 10

and 15. The client knows nothing of those changes in the

repository, since you haven't yet run svn

update, and svn commit doesn't

pull down new changes. If, on the other hand,

svn commit were to automatically download

the newest changes, then it would be possible to set the

entire working copy to revision 15—but then we'd be

breaking the fundamental rule of “push”

and “pull” remaining separate actions.

Therefore, the only safe thing the Subversion client can do

is mark the one

file—foo.html—as being at

revision 15. The rest of the working copy remains at

revision 10. Only by running svn update

can the latest changes be downloaded and the whole working

copy be marked as revision 15.

The fact is, every time you run svn commit, your working copy ends up with some mixture of revisions. The things you just committed are marked as having larger working revisions than everything else. After several commits (with no updates in between), your working copy will contain a whole mixture of revisions. Even if you're the only person using the repository, you will still see this phenomenon. To examine your mixture of working revisions, use the svn status --verbose command (see the section called “See an overview of your changes” for more information.)

Often, new users are completely unaware that their working copy contains mixed revisions. This can be confusing, because many client commands are sensitive to the working revision of the item they're examining. For example, the svn log command is used to display the history of changes to a file or directory (see the section called “Generating a List of Historical Changes”). When the user invokes this command on a working copy object, they expect to see the entire history of the object. But if the object's working revision is quite old (often because svn update hasn't been run in a long time), then the history of the older version of the object is shown.

If your project is sufficiently complex, you'll discover that it's sometimes nice to forcibly backdate (or, update to a revision older than the one you already have) portions of your working copy to an earlier revision; you'll learn how to do that in Chapter 2, Basic Usage. Perhaps you'd like to test an earlier version of a submodule contained in a subdirectory, or perhaps you'd like to figure out when a bug first came into existence in a specific file. This is the “time machine” aspect of a version control system—the feature that allows you to move any portion of your working copy forward and backward in history.

However you make use of mixed revisions in your working copy, there are limitations to this flexibility.

First, you cannot commit the deletion of a file or directory that isn't fully up to date. If a newer version of the item exists in the repository, your attempt to delete will be rejected in order to prevent you from accidentally destroying changes you've not yet seen.

Second, you cannot commit a metadata change to a directory unless it's fully up to date. You'll learn about attaching “properties” to items in Chapter 3, Advanced Topics. A directory's working revision defines a specific set of entries and properties, and thus committing a property change to an out-of-date directory may destroy properties you've not yet seen.

We've covered a number of fundamental Subversion concepts in this chapter:

We've introduced the notions of the central repository, the client working copy, and the array of repository revision trees.

We've seen some simple examples of how two collaborators can use Subversion to publish and receive changes from one another, using the “copy-modify-merge” model.

We've talked a bit about the way Subversion tracks and manages information in a working copy.

At this point, you should have a good idea of how Subversion works in the most general sense. Armed with this knowledge, you should now be ready to move into the next chapter, which is a detailed tour of Subversion's commands and features.

Table of Contents

Now we will go into the details of using Subversion. By the time you reach the end of this chapter, you will be able to perform all the tasks you need to use Subversion in a normal day's work. You'll start with getting your files into Subversion, followed by an initial checkout of your code. We'll then walk you through making changes and examining those changes. You'll also see how to bring changes made by others into your working copy, examine them, and work through any conflicts that might arise.

Note that this chapter is not meant to be an exhaustive list of all Subversion's commands—rather, it's a conversational introduction to the most common Subversion tasks that you'll encounter. This chapter assumes that you've read and understood Chapter 1, Fundamental Concepts and are familiar with the general model of Subversion. For a complete reference of all commands, see Chapter 9, Subversion Complete Reference.

Before reading on, here is the most important command you'll

ever need when using Subversion: svn help.

The Subversion command-line client is self-documenting—at

any time, a quick svn help

SUBCOMMAND will describe

the syntax, options, and behavior of the subcommand.

$ svn help import

import: Commit an unversioned file or tree into the repository.

usage: import [PATH] URL

Recursively commit a copy of PATH to URL.

If PATH is omitted '.' is assumed.

Parent directories are created as necessary in the repository.

If PATH is a directory, the contents of the directory are added

directly under URL.

Unversionable items such as device files and pipes are ignored

if --force is specified.

Valid options:

-q [--quiet] : print nothing, or only summary information

-N [--non-recursive] : obsolete; try --depth=files or --depth=immediates

--depth ARG : pass depth ('empty', 'files', 'immediates', or

'infinity') as ARG

…

There are two ways to get new files into your Subversion repository: svn import and svn add. We'll discuss svn import now and will discuss svn add later in this chapter when we review a typical day with Subversion.

The svn import command is a quick way to copy an unversioned tree of files into a repository, creating intermediate directories as necessary. svn import doesn't require a working copy, and your files are immediately committed to the repository. This is typically used when you have an existing tree of files that you want to begin tracking in your Subversion repository. For example:

$ svnadmin create /var/svn/newrepos

$ svn import mytree file:///var/svn/newrepos/some/project \

-m "Initial import"

Adding mytree/foo.c

Adding mytree/bar.c

Adding mytree/subdir

Adding mytree/subdir/quux.h

Committed revision 1.

The previous example copied the contents of directory

mytree under the directory

some/project in the repository:

$ svn list file:///var/svn/newrepos/some/project bar.c foo.c subdir/

Note that after the import is finished, the original tree is not converted into a working copy. To start working, you still need to svn checkout a fresh working copy of the tree.

While Subversion's flexibility allows you to lay out your

repository in any way that you choose, we recommend that you

create a trunk directory to hold the

“main line” of development, a

branches directory to contain branch

copies, and a tags directory to contain tag

copies—for example:

$ svn list file:///var/svn/repos /trunk /branches /tags

You'll learn more about tags and branches in Chapter 4, Branching and Merging. For details and how to set up multiple projects, see the section called “Repository Layout” and the section called “Planning Your Repository Organization” to read more about project roots.

Most of the time, you will start using a Subversion

repository by doing a checkout of your

project. Checking out a repository creates a “working

copy” of it on your local machine. This copy contains

the HEAD (latest revision) of the Subversion

repository that you specify on the command line:

$ svn checkout http://svn.collab.net/repos/svn/trunk A trunk/Makefile.in A trunk/ac-helpers A trunk/ac-helpers/install.sh A trunk/ac-helpers/install-sh A trunk/build.conf … Checked out revision 8810.

Although the above example checks out the trunk directory, you can just as easily check out any deep subdirectory of a repository by specifying the subdirectory in the checkout URL:

$ svn checkout \

http://svn.collab.net/repos/svn/trunk/subversion/tests/cmdline/

A cmdline/revert_tests.py

A cmdline/diff_tests.py

A cmdline/autoprop_tests.py

A cmdline/xmltests

A cmdline/xmltests/svn-test.sh

…

Checked out revision 8810.

Since Subversion uses a “copy-modify-merge” model instead of “lock-modify-unlock” (see the section called “Versioning Models”), you can start right in making changes to the files and directories in your working copy. Your working copy is just like any other collection of files and directories on your system. You can edit and change them, move them around, even delete the entire working copy and forget about it.

Warning

While your working copy is “just like any other collection of files and directories on your system,” you can edit files at will, but you must tell Subversion about everything else that you do. For example, if you want to copy or move an item in a working copy, you should use svn copy or svn move instead of the copy and move commands provided by your operating system. We'll talk more about them later in this chapter.

Unless you're ready to commit the addition of a new file or directory or changes to existing ones, there's no need to further notify the Subversion server that you've done anything.

While you can certainly check out a working copy with the URL of the repository as the only argument, you can also specify a directory after your repository URL. This places your working copy in the new directory that you name. For example:

$ svn checkout http://svn.collab.net/repos/svn/trunk subv A subv/Makefile.in A subv/ac-helpers A subv/ac-helpers/install.sh A subv/ac-helpers/install-sh A subv/build.conf … Checked out revision 8810.

That will place your working copy in a directory named

subv instead of a directory named

trunk as we did previously. The directory

subv will be created if it doesn't already

exist.

When you perform a Subversion operation that requires you to authenticate, by default Subversion caches your authentication credentials on disk. This is done for convenience, so that you don't have to continually re-enter your password for future operations. If you're concerned about caching your Subversion passwords, [3] you can disable caching either permanently or on a case-by-case basis.

To disable password caching for a particular one-time

command, pass the --no-auth-cache option on

the command line. To permanently disable caching, you can add

the line store-passwords = no to your local

machine's Subversion configuration file. See the section called “Client Credentials Caching” for

details.

Since Subversion caches auth credentials by default (both

username and password), it conveniently remembers who you were

acting as the last time you modified you working copy. But

sometimes that's not helpful—particularly if you're

working in a shared working copy such as a system

configuration directory or a webserver document root. In this

case, just pass the --username option on the

command line, and Subversion will attempt to authenticate as

that user, prompting you for a password if necessary.

Subversion has numerous features, options, bells, and whistles, but on a day-to-day basis, odds are that you will only use a few of them. In this section, we'll run through the most common things that you might find yourself doing with Subversion in the course of a day's work.

The typical work cycle looks like this:

Update your working copy.

svn update

Make changes.

svn add

svn delete

svn copy

svn move

Examine your changes.

svn status

svn diff

Possibly undo some changes.

svn revert

Resolve conflicts (merge others' changes).

svn update

svn resolved

Commit your changes.

svn commit

When working on a project with a team, you'll want to update your working copy to receive any changes made since your last update by other developers on the project. Use svn update to bring your working copy into sync with the latest revision in the repository:

$ svn update U foo.c U bar.c Updated to revision 2.

In this case, someone else checked in modifications to

both foo.c and bar.c

since the last time you updated, and Subversion has updated

your working copy to include those changes.

When the server sends changes to your working copy via svn update, a letter code is displayed next to each item to let you know what actions Subversion performed to bring your working copy up-to-date. To find out what these letters mean, see svn update.

Now you can get to work and make changes in your working copy. It's usually most convenient to decide on a discrete change (or set of changes) to make, such as writing a new feature, fixing a bug, etc. The Subversion commands that you will use here are svn add, svn delete, svn copy, svn move, and svn mkdir. However, if you are merely editing files that are already in Subversion, you may not need to use any of these commands until you commit.

There are two kinds of changes you can make to your working copy: file changes and tree changes. You don't need to tell Subversion that you intend to change a file; just make your changes using your text editor, word processor, graphics program, or whatever tool you would normally use. Subversion automatically detects which files have been changed, and in addition, handles binary files just as easily as it handles text files—and just as efficiently too. For tree changes, you can ask Subversion to “mark” files and directories for scheduled removal, addition, copying, or moving. These changes may take place immediately in your working copy, but no additions or removals will happen in the repository until you commit them.

Here is an overview of the five Subversion subcommands that you'll use most often to make tree changes.

- svn add foo

Schedule file, directory, or symbolic link

footo be added to the repository. When you next commit,foowill become a child of its parent directory. Note that iffoois a directory, everything underneathfoowill be scheduled for addition. If you want only to addfooitself, pass the--non-recursive(-N) option.- svn delete foo

Schedule file, directory, or symbolic link

footo be deleted from the repository. Iffoois a file or link, it is immediately deleted from your working copy. Iffoois a directory, it is not deleted, but Subversion schedules it for deletion. When you commit your changes,foowill be entirely removed from your working copy and the repository. [4]- svn copy foo bar

Create a new item

baras a duplicate offooand automatically schedulebarfor addition. Whenbaris added to the repository on the next commit, its copy history is recorded (as having originally come fromfoo). svn copy does not create intermediate directories unless you pass the--parents.- svn move foo bar

This command is exactly the same as running svn copy foo bar; svn delete foo. That is,

baris scheduled for addition as a copy offoo, andfoois scheduled for removal. svn move does not create intermediate directories unless you pass the--parents.- svn mkdir blort

This command is exactly the same as running mkdir blort; svn add blort. That is, a new directory named

blortis created and scheduled for addition.

Once you've finished making changes, you need to commit them to the repository, but before you do so, it's usually a good idea to take a look at exactly what you've changed. By examining your changes before you commit, you can make a more accurate log message. You may also discover that you've inadvertently changed a file, and this gives you a chance to revert those changes before committing. Additionally, this is a good opportunity to review and scrutinize changes before publishing them. You can see an overview of the changes you've made by using svn status, and dig into the details of those changes by using svn diff.

Subversion has been optimized to help you with this task,

and it is able to do many things without communicating with

the repository. In particular, your working copy contains a

hidden cached “pristine” copy of each version

controlled file within the .svn area.

Because of this, Subversion can quickly show you how your

working files have changed or even allow you to undo your

changes without contacting the repository.

To get an overview of your changes, you'll use the svn status command. You'll probably use svn status more than any other Subversion command.

If you run svn status at the top of

your working copy with no arguments, it will detect all file

and tree changes you've made. Below are a few examples of

the most common status codes that svn

status can return. (Note that the text following

# is not

actually printed by svn status.)

? scratch.c # file is not under version control A stuff/loot/bloo.h # file is scheduled for addition C stuff/loot/lump.c # file has textual conflicts from an update D stuff/fish.c # file is scheduled for deletion M bar.c # the content in bar.c has local modifications

In this output format, svn status prints six columns of characters, followed by several whitespace characters, followed by a file or directory name. The first column tells the status of a file or directory and/or its contents. The codes we listed are:

A itemThe file, directory, or symbolic link

itemhas been scheduled for addition into the repository.C itemThe file

itemis in a state of conflict. That is, changes received from the server during an update overlap with local changes that you have in your working copy (and weren't resolved during the update). You must resolve this conflict before committing your changes to the repository.D itemThe file, directory, or symbolic link

itemhas been scheduled for deletion from the repository.M itemThe contents of the file

itemhave been modified.

If you pass a specific path to svn status, you get information about that item alone:

$ svn status stuff/fish.c D stuff/fish.c

svn status also has a

--verbose (-v) option,

which will show you the status of every

item in your working copy, even if it has not been

changed:

$ svn status -v

M 44 23 sally README

44 30 sally INSTALL

M 44 20 harry bar.c

44 18 ira stuff

44 35 harry stuff/trout.c

D 44 19 ira stuff/fish.c

44 21 sally stuff/things

A 0 ? ? stuff/things/bloo.h

44 36 harry stuff/things/gloo.c